When are Trademarks Deceptive? Comparing Food and Drug Trademarks in Taiwan and China

Date: 4 January, 2023

【Volume 98】

Since food and drug respectively relates to food and medication safety which are vital issues concerning the life and physical health of consumers, the China National Intellectual Property Administration (“CNIPA”) is more stringent with food and pharmaceutical trademark examinations We have previously covered this issue in "Protecting pharmaceutical trademarks in China and Taiwan", listing the cases regarding the Trademark Act regulations and examination of pharmaceutical trademark registrations in China and Taiwan.

According to the above-mentioned article, the CNIPA is particularly rigorous when examining “descriptive terms that indicate raw material or function of goods” and “deceptive marks that mislead the consumers”, resulting in difficulties for applicants to navigate the thin line between distinctiveness and deceptiveness when adopting homophones or metaphors in trademark designs. In addition, applicants do not know how to overcome the rejection concerning deceptiveness since there is no related examination guideline.

On the other hand, according to Taiwan Trademark Act and the examination guidelines published by Taiwan Intellectual Property Office (TIPO), there is no certain criterion for determining whether a term has the likelihood of misleading the public as to the property, quality or place of origin of the goods and services; nevertheless, other authorities in Taiwan gave explicit guidelines for the naming of individual goods and trademark representations, which would be put into consideration by the TIPO when examining trademarks.

This article further introduces the examination practices in relation to the regulations of misconception and deceptiveness in food/pharmaceutical trademarks and the criteria of judgment, by TIPO and Chinese courts.

Examination Criteria and Case Studies of Chinese Courts’ Response to Deceptiveness Provision

1. Clarify whether a trademark’s name is descriptive while referring to the common knowledge and cognitive ability of the public:

|

(Registration Number: 44824177) |

Class 33 Fruit wine containing alcohol; wine; liquors, as beverages; alcoholic extracts; alcoholic beverages, except beer; alcoholic beverages containing fruit; rice alcohol; yellow rice liquors; Chinese white wine; white distilled spirit. |

|

Judgment No.: (2022) Jingxingzhong No. 1898 Administrative Judgment (administrative suit over trademark rejection review) |

|

Case Fact

Formerly a distillery, Luzhou Laojiao Co. Ltd (“Luzhou Laojiao”) is a company with a hundred-year-old distillation craftsmanship history. The company is widely known for its white spirit brand — “National Cellar 1573”, distilled in the treasure-class national cellars built in 1573. In addition, “National Cellar 1573” was chosen as the representative of both national tangible and intangible cultural heritage.

Luzhou Laojiao filed the application of trademark “National Cellar (国窖)” with CNIPA on March 23, 2020; however, CNIPA refused it on the basis of that the usage of said trademark on designated goods is likely to mislead consumers about the quality and characteristics of goods. Luzhou Laojiao thus filed a review of rejection and an administrative lawsuit; however, both the CNIPA and the first-instance court upheld the aforementioned decision and reason for rejection. Luzhou Laojiao then appealed to the court of second-instance and the court overruled the rulings by the court of first-instance.

Opinions of the Appeal Court

(1) The meaning of the term “National Cellar (国窖)” does not describe the content of goods such as fruit wine (containing alcohol) and wine, and thus the term is unlikely to mislead the public about its quality and characteristics.

(2) The term “National Cellar” originated in and only in the “treasure-class national cellars” built in 1573 by Luzhou Laojiao company. In addition, the cellars are under multiple protection measures by the Government; therefore, “National Cellar” being a trademark would not cause misunderstandings among the consumers over the quality and characteristics of the goods.

(3) Luzhou Laojiao company has already used “National Cellar” as the brand of alcohol products designated in Class 33, and widely registered the trademark as well. Moreover, “National Cellar” was recognized as a well-known trademark with a strong awareness among consumers; namely, a stable perception of the concept of “National Cellar” was formed. Accordingly, having an exclusive relationship with the Luzhou Laojiao company, the use of the trademark “National Cellar” would not lead to misconceptions toward the quality and characteristics of goods among consumers.

2. Even if a trademark contains a descriptive term, designated goods should be examined term by term to determine whether it is deceptive:

|

(Registration Number: 44050872) |

Class 29 Goat’s milk powder; goat’s milk; solid-state milk; buttermilk; milk; milk powder; dairy product. |

|

Judgment No.: (2021) Jingxingzhong No. 7854 Administrative Judgment (administrative suit over trademark rejection review) |

|

Case Fact

The Inner Mongolia Yili Industrial Group Co., Ltd (“Yili”) has specialized in dairy products for years with its Chinese life-nurturing concept family products’ trademark successfully registered, such as “骨能膳底” (meaning bone, ability, rice meal, base in literal translation) and “Xinhuo (心活)” (meaning heart, live in literal translation), both containing Chinese life-nurturing ingredients.

However, the application for trademark “纾糖膳底” (meaning to relieve, sugar, rice meal, base in literal translation) for the new family products’ brand in February 2020 was blocked by CNIPA based on that the character “纾” means “to relieve,to slow” in Chinese, which is likely to mislead the consumers about the quality and characteristics of goods if used as a trademark in designated goods. Yili then filed a review of rejection and a first-instance administrative lawsuit, but the CNIPA and first-instance court both maintained the aforementioned reason for rejection. Thus, Yili filed an appeal and the first-instance court’s rulings were partially overruled by the second-instance court.

Opinions of the Appeal Court

(1) Although the character “纾” undoubtedly has the meaning of “to relieve, to slow”, according to the business association’s documents filed by Yili and product evaluation report issued by professional facilities, Yili’s “纾糖膳底” milk powder does in fact slow down the digestion and absorbance of glucose and carbohydrates, thus attaining the result of lowering, improving, and controlling the level of postprandial blood sugar. Therefore, even if the trademark “纾糖膳底” means slowing down sugar in Chinese, it is not deceptive when used on designated goods of goat’s milk powder, goat’s milk, solid-state milk, buttermilk, milk, milk powder, and dairy product.

(2) On the other hand, the other designated goods in this case, namely fruit-and-vegetable-based snack food, meat, edible seaweed extract, non-living fish, tinned fruits, and pickled fruits, remain to be determined as deceptive, upholding the decision by the first-instance court.

3. Whether foreign language terms within trademarks are deceptive should depend on published dictionaries:

|

(Registration Number: 28053967) |

Class 5 Pharmaceutical preparations; nutritional supplement for medical use; mineral food supplements. |

|

Judgment No.: (2020) Jingxingzhong No. 2878 Administrative Judgment (administrative suit over trademark rejection review) |

|

Case Fact

Entasis Therapeutics (“Entasis”), a world-famous antibiotic resistance therapy development corporation, filed a trademark application in 2017 with CNIPA using the name of the company as the design of the logo. However, the application was determined as a deceptive trademark and was refused based on the term “entasis” meaning “shape of a bulging abdomen” and the term “therapeutics” meaning “medical therapy” in English, which is said to be misleading about the function and intended purpose of the designated goods in class 5 “pharmaceutical preparations” among consumers. Entasis then filed a review of rejection and a first-instance administrative lawsuit, but the CNIPA and first-instance court both maintained the aforementioned reason for rejection. Thus, Yili filed an appeal and the first-instance court’s rulings were partially overruled by the second-instance court.

Opinions of the Appeal Court

(1) The term “entasis” was not in the medical dictionaries, including Longman Medical Dictionary, submitted by the company Entasis. Furthermore, though the term was in the comprehensive English/ Chinese dictionary, “entasis” was defined as “a slight convexity, especially in the shaft of a column”, which does not match the “shape of a bulging abdomen” meaning mentioned in the notification of rejection and review of rejection.

(2) Further, the trademark “ENTASIS THERAPEUTICS” is not an existing English term in said dictionaries. Even if the second part of the term “THERAPEUTICS” has the meaning of medical therapy, it would not mislead the relevant public as to the function and intended purpose of designated goods, such as pharmaceutical preparation; consequently, the trademark “ENTASIS THERAPEUTICS” should not be determined as deceptive.

Examination Criteria and Case Studies of Taiwan Courts’ Response to Misleading Terms

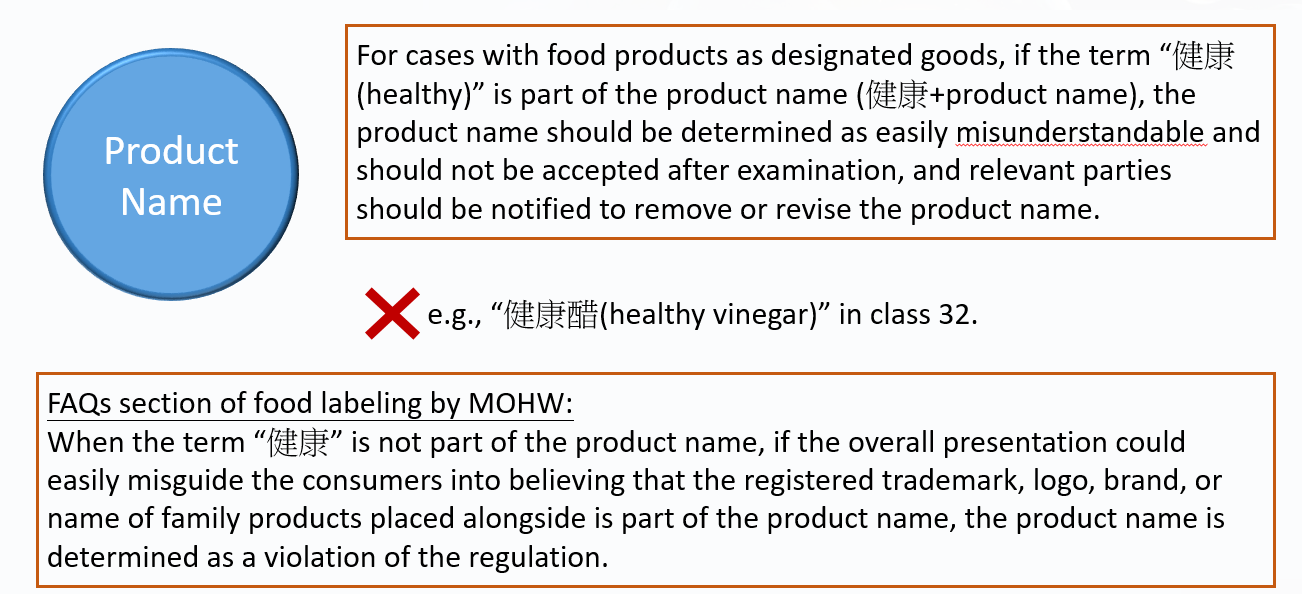

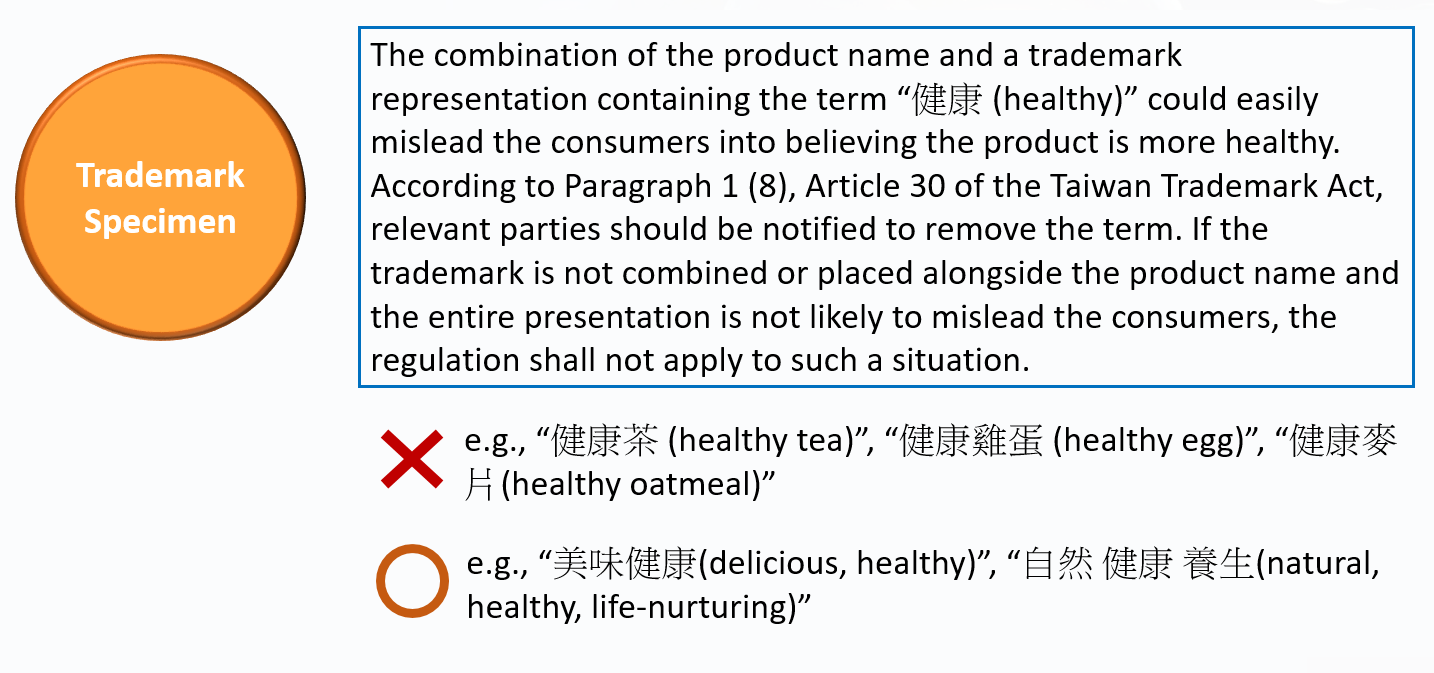

According to the forepart of Paragraph 2, Article 4 of the “Regulations Governing of Criteria for the Label, Promotion and Advertisement of Foods and Food Products Identified as False, Exaggerated, Misleading or Having Medical Efficacy” by the Ministry of Health and Welfare (“MOHW”), if the word “health” is part of the food product name, it is identified as misleading. The IPO will apply this regulation when examining trademarks. Recent examination practices are exemplified as follows.

Examples of Opinions of IPO on Examination

1. For cases with food products as designated goods, the term “健康 (healthy)” is required to be removed from the product name. E.g., “健康醋 (healthy vinegar)” should be “醋 (vinegar)” instead.

2. For cases with the term “健康” as part of the trademark representation, if there is a likelihood of misunderstanding, the trademark should be determined as a violation of the provision in the Taiwan Trademark Act for being likely to mislead the public as to the nature, quality, or place of origin of the goods or services , and the relevant parties should be notified to remove the term. e.g., The term “健康麥片 (healthy oatmeal)” should be removed from the trademark representation.

Wisdom Suggested Strategies

For the benefits of marketing and retailing of food and medicine, relevant providers tend to adopt terms about the effects or ingredients of the product, or terms with double meanings or homophone puns as part of the logo design, in order to raise brand awareness among consumers and increase their purchase intentions. However, in China, trademarks with “descriptive” or “suggestive” terms are more likely to be rejected by CNIPA during the application phase due to violation of the deceptiveness provision. According to the above opinions, the CNIPA and Chinese Courts have developed more specific and rigorous examination guidelines toward the deceptiveness provision under Paragraph 1 (7), Article 10 of the China Trademark Law.

Taking the first case mentioned above (“国窖班”) as an example, to identify whether a trademark term is deceptive, namely, misleading for the public, the first thing to do is to make sure whether the term has a certain descriptive meaning or not. If it is merely a fictional term, without a doubt, the trademark would not misguide the public regarding the quality and characteristics of the goods. As for the second example “纾糖膳底”, even if the term has a specific descriptive meaning, all designated goods should be examined thoroughly to determine whether it is deceptive individually; for the ones being determined as exaggerated and unrealistic, applicants can also file professional reports issued by credible third-party facilities as evidence to respond to reasons for refusal. Moreover, the purpose of the regulations prohibiting deceptiveness is to prevent consumers from making false purchases under a misconception, namely that “whether the common knowledge and cognitive ability of the public is misguided” is one of the vital issues of these type of cases; thus, brand awareness or objective evidence shall be helpful when responding to reasons of refusal. Applicants can refer to the abovementioned guidelines during the phase of review or even the following administrative lawsuit, and consult with professional trademark agents to prepare evidence for responding to the reasons for refusal.

As for the practice of trademark examination in Taiwan, other than the "Regulations Governing of Criteria for the Label, Promotion and Advertisement of Foods and Food Products Identified as False, Exaggerated, Misleading or Having Medical Efficacy" mentioned in the examination opinions by TIPO, "Regulations Governing Criteria for the Label, Promotion, Advertisement with Deception, Exaggeration, or Medical efficacy of Cosmetic Products" by MOHW are also referred to when examining cosmetic and hair care products. Consequently, applicants should be alert that if a trademark includes any term that violates the aforementioned regulations, not only may the application be rejected, but also a violation of the law is possible due to using such terms.